Be sure to sign up for the Art Center Information newsletter and enter to win a free coffee table art book>>>

I recall when I was about thirteen years old that I painted a picture of a horse. I did this with no reference, simply from memories in my mind, and I thought I’d done a pretty good job of it. Proudly, I taped it to the wall of my bedroom, hoping my father, artist, Arlen Burton, would notice it. He did. The conversation went something like this: “Who painted the picture of the horse, son? Did you do that?”

“Yes I did,” I said, proudly.

My father stared at it for a time, and then he said, “You need to study foreshortening.” And then he went on his way.

Foreshortening! I thought. What is foreshortening? Obviously, I was deflated. However, I began to study foreshortening. What seemed at the time to be a devastating criticism became a great motivator.

The best example of foreshortening is the poster where Uncle Sam points his finger at you. Foreshortening flattens out and shortens the length of an object to stimulate perspective. Anything you see at an angle, not straight on, is foreshortening.

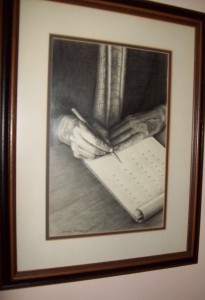

In James Frederick’s drawing at the right, foreshortening is prevalent in the hands and the paper pad. It is easy for us to think of foreshortening when considering round objects such as fingers, arms, legs, and even tree limbs, but rectangular objects are foreshortened as well–their sides are seen as shorter than they are. Everything has to be kept in perspective.

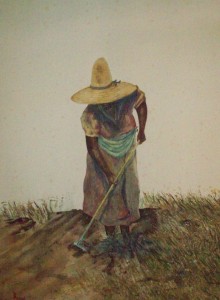

In my watercolor study to the left, I am not entirely pleased with the foreshortening on the left arm. When I paint it in acrylic, I intend to dip her head a bit more while tilting the hat and show more foreshortening of the upper arm. I’ll sketch it with a model to see if I’m right. Whatever, foreshortening can be very deceiving.

Remember when considering foreshortening to keep in mind it is perspective. Paint or draw receding lines shorter than they are. You must present an illusion of depth.